February 9, 2026

Connect Music: Black-Owned Music Rights Tech Firm Hits $80M Milestone

With the new financing, Connect Music will have the opportunity to scale its acquisition and licensing strategy.

Connect Music, a Black-owned music rights and tech company based in Memphis, just hit an $80 million milestone. The company reached this achievement with Rockmont Partners and Variant Investments.

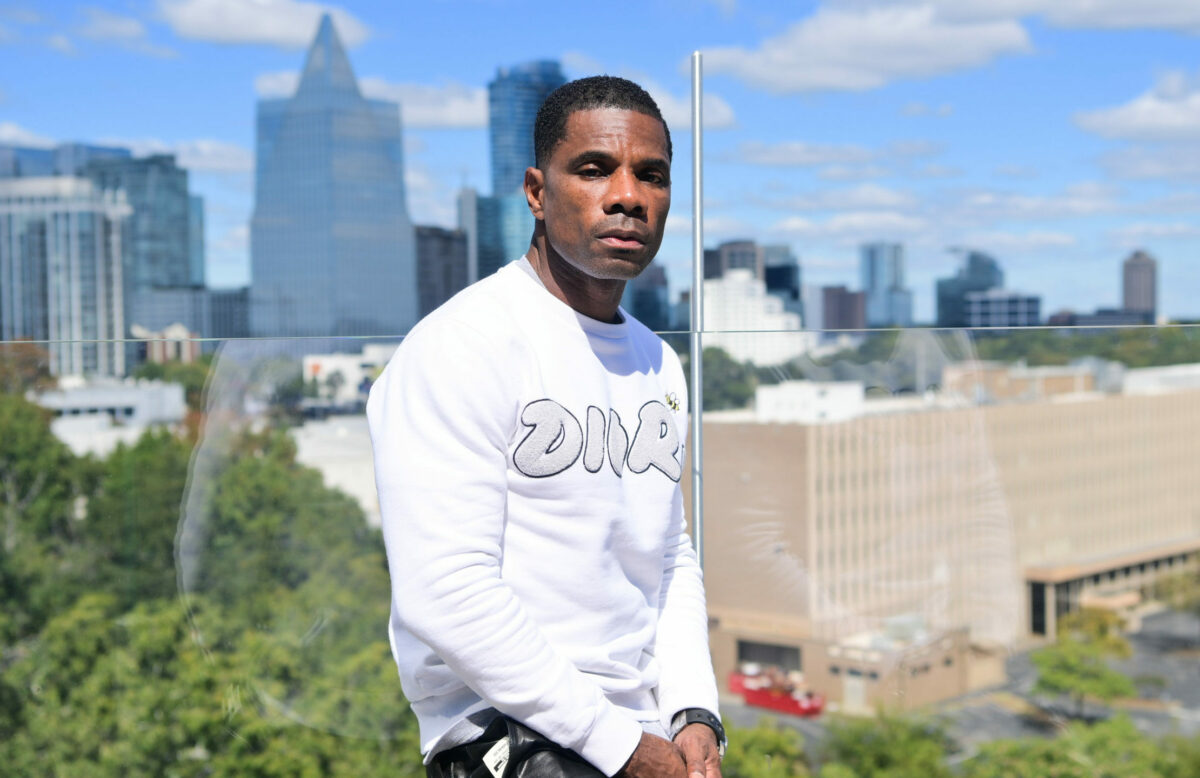

The new financing positions Connect Music for significant growth in catalog acquisition, music licensing, and data-driven solutions. It’s a move that the company’s CEO, George Monger, said will empower independent artists and labels.

“This investment represents transformational growth capital for Connect Music and the artist partners we serve,” said Monger. “It gives us the ability to grow aggressively while staying true to our mission: empowering creators to maximize their earnings while owning their art, their data, and their future.”

Connect Music Expanding Opportunity For Independent Artists and Labels

Monger began his career managing an international opera singer on tour and later launched a nonprofit music organization. He served as Chief Operating Officer of the Memphis Symphony Orchestra for four years before launching Connect Music in 2020.

He set out to provide independent artists and labels with transparent technology and financing typically reserved for key industry players.

“We have seen Connect accelerate from a bold vision into a scaled, high-performing business,” said Curt Futch, managing director at Rockmont Partners. “George’s ability to pair operational discipline with a deep commitment to creators has been a differentiator at every stage, and we have been impressed with how he executes on his plans.”

With the new financing, Connect Music will have the opportunity to scale its acquisition and licensing strategy and deploy proprietary AI models that could allow artists to earn more from their intellectual property.

“Managing artists and running a nonprofit taught me that talent alone isn’t enough- artists deserve systems that honor their creativity and secure their future,” Monger added. “My mission is to redefine what it means to win in music: where ownership, education, and empowerment coexist. This investment allows us to scale while keeping creators at the center of every decision.”

RELATED CONTENT: Kendrick Lamar’s ‘GNX’ First Hip-Hop Album To Sell 1 Million Units In 2025