Redlining, as defined by Cornell University’s Legal Information Institute, is a discriminatory practice characterized by the deliberate refusal of essential services like mortgages, insurance loans, and various financial services to inhabitants of specific regions based solely on their racial or ethnic background. Data from the Federal Reserve suggests that Black people are twice as likely as white people to be denied credit, regardless of their income level. This impacts mortgage loans. A potential solution to this designed inequality is the emergence or re-emergence of Black-owned banks, reports Forbes Advisor.

Between 1888 and 1934, 134 Black-owned banks were formed in an attempt to assist Black borrowers with securing credit and other monetary services, according to One United Bank. Today, the number of Black-owned banks sits at 42, reports Finder. Furthermore, to qualify as a Black-owned bank, an institution must be at least 51% Black-owned and serve a population of mostly minorities.

One United, considered the largest Black-owned bank in America, holds around $625 million in assets, compared to Bank of America, which holds approximately $2.5 trillion. This value difference is comparable to the difference in wealth between Black and white citizens in America. According to data from the Federal Reserve, the average Black family’s wealth is six times less than the average white family’s wealth. While wealth is not income, it is difficult to accrue wealth with lower income levels, evidenced by the Fed’s data showing that the Black/white wealth gap widened despite a faster growth in wealth for Black families in 2022.

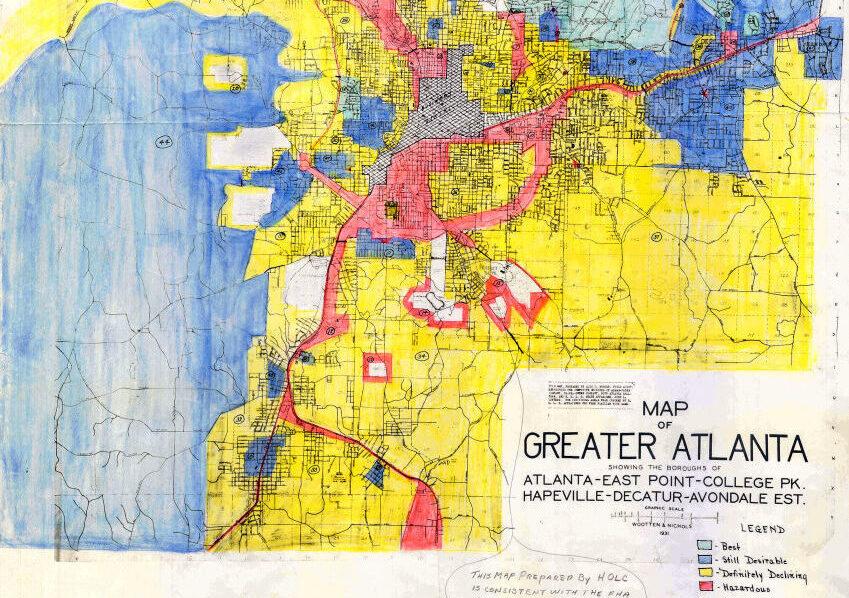

The historical practice in America of redlining was created by the United States government’s New Deal through the Federal Home Owners Loan Corporation, which created color-coded maps showing high-risk lending areas in red. Those red-lined areas tended to be populated by Black people, which meant, essentially, that Black people were blocked from participating in homeownership, a key cog in wealth creation. “Redlining was part of a systemic, codified policy by the government, mortgage lenders, real estate developers and real estate agents as a bloc to deprive Black people of homeownership,” according to Rajeh Saadeh, a real estate and civil rights attorney in Bridgewater, New Jersey. “The ramifications of this practice have been generational.”

Black-owned banks might not be the only solution to the legacy of redlining.

Michel Martin of PBS discussed how banking deserts exacerbate the wealth gap in America in a 2020 interview with Mehrsa Baradaran, author of The Color of Money: Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap.

Baradaran, an Iranian-American law professor specializing in banking law at the University of California, Irvine, suggested to Martin that a postal banking system could help offset costs associated with traditional banking.

“So, what happens in these areas is, people have to drive 30 miles to an ATM and a 7-Eleven and pay $7.50, right? Or they can go to Walmart or a payday lender or a check cashier to get their financial transactions. And so the idea with the postal bank is to actually have the post office, which, by its original mission, is in every community, just allow for simple banking,” said Baradaran.

He continued, “So this is a debit card, so you can participate in nationwide commerce and a checking account, so you can pay your bills online, and not have to operate in cash. It’s just a simple idea, I think, that would benefit a ton of communities, not just Black and brown committees, but certainly also to that.”

While Baradaran admits that it is not a complete solution to the issue of the racial wealth gap, she says the nature of that arrangement requires a much more concentrated effort, one that would go a long way in providing some assistance to the estimated 25% of the Black population that is currently operating without access to traditional banking methods.

RELATED CONTENT: The Atlanta Hawks Become First Sports Franchise To Secure Financing From Black-Owned Banks